Shortly before we plunge into the cold of winter, One Eleven Heavy will be bringing the last of the summer sun with their unique brand of singed folk rock.

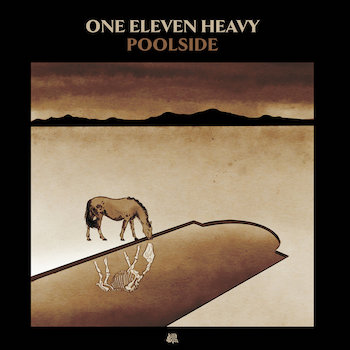

On November 4th, the international group’s eagerly anticipated third studio effort, Poolside will be unleashed by Kith & Kin Records.

I recently spoke with the band’s founding members, Nick Mitchell Maiato and James Toth, about the new album, the challenges of working remotely and Sasquatch, among other things. Check it out:

RCU: Quite a lot has come to pass since the last One Eleven Heavy record—obviously the pandemic probably being the biggest one. So I imagine that you had to adjust your vision of the new album over the last couple years. So what was the initial direction you guys wanted the record to go in at its inception. And how did that vision differ from the final product?

Nick Mitchell Maiato: I had resent an email to James where I think we ended the conversation about the record with me talking about Gothic Western, and I realized that I’d sent this email a couple of years back, saying like ‘the next one should be like a Gothic Western record’. And then I started to bang on about it at the end of the process too, without realizing I’d ever mentioned it before. And I don’t think James remembered that I’d mentioned it before.

I always had this vision in my mind of David Crosby’s first solo record, If Only I Could Remember My Name. There are a few moments in the “Cowboy Movie” song that reminded me of the Richard Brautigan book, The Hawkline Monster. And I think that I started to make a twisted connection between those, the book and that record, even though the book came out five years after that record. I think that in my mind’s ear, I was thinking I want to make something really kind of sun scorched. I’m living here in Spain, and it’s a new world for me. I want to absorb some of its influence, some of its good vibes. I think I misinterpreted that in terms of the way I was writing, at least for this record. I think James did too actually, but I don’t think what we ended up with was necessarily what you might have imagined the brief Gothic Western to be, but yeah, that’s where we began. You want to talk about the process, James?

James Toth: Well, I’ll concede that, Nick really had to twist my arm at first to agree to do this remotely. I mean I think working remotely, if you’re making techno or something like prog rock even, you could probably pull it off, but we rely so much on feel and improvisation and happy little accidents and stuff. So I had a hard time at first trying to see how we were going to do that, but I’m really glad that Nick talked me into it. Nick talks me into almost everything. He’s very persuasive about many things but he made it work and I really embraced it. I started to really enjoy it as a different process. I mean, I definitely want us to all be in the same room to do the next record, if at all possible. I don’t want this to be the new normal, but yeah, I really enjoyed working this way and it gave us a lot of more time to reflect on what we were doing, what we were playing.

RCU: What were some of the hardest parts when it came to recording through file sharing?

JT: I think Nick should get most of the credit. I mean, Nick did a lot of the heavy lifting as far as engineering and arranging things. It went pretty smoothly. I have to say. I don’t remember any crisis moments, and I can’t say that about records that any of us have made together or apart in the studio. There’s always a crisis moment. And this one, there really wasn’t. Maybe Nick has a different perspective, but it was pretty easy.

NM: Yeah. You have time to reflect.

JT: Yeah, exactly.

NM: A lot of time to reflect on decisions. When you’re in a studio, you have such a short amount of time to come to decisions because you’re on the clock, and arguments occur as a result. And James and I have had them. I think with this record, there was a song on the record that James was insistent for a long time was going to be the side-A track one, but I was unsure I even wanted to put that song on the record. Yet, because we had time to reflect in our own space, we were able to email about this.mail’s not always the best form of communication, because lots of misunderstandings occur that way, but it seemed to work for us. I think that’s down to just having similar goals and similar outlooks and tastes. I think there’s enough crossover between us to exert a little patience when needed.

JT: Not to be too ambiguous, but without naming the song, I’ll say that the compromise was reached because the song is on the record, but it’s not the first [track]. Just really briefly about the pandemic: The one thing I do want to mention is that while recording remotely was definitely a challenge, this is a band that always sort of had that sort of challenge because at one point, I think the two closest members geographically were like 600 miles [apart]. We’ve always been spread out. So not seeing each other every day was something we were pretty much used to anyway. So yeah, there were challenges, but I think probably we had fewer challenges on that front than a lot of bands, you know?

RCU: Yeah. That’s true. So on that note, at least in the past, I’ve always been curious how much time did you guys typically get to rehearse together before doing a tour?

NM: A day, two days.

JT: Yeah. A few days [laughs] we practiced at home, though.

RCU: I know some members are no longer a part of the band. So what were you generally looking for while trying to track down [bass and piano] replacements?

NM: It was kind of fortunate timing in a way with the bass situation, just because I’d been looking for people to play my solo material with here in Spain. I came across this British guy called Guy, who lives here in the city and in Valencia. He was amazing. He sent me some of his music, and I wasn’t totally into the stuff, but his playing was exceptional, and he seemed like a really cool guy. So I suggested that he take a crack at one of the more problematic songs. And when he sent it back, he sort of, he sent me back a problematic version of it. Which was, it was like, ‘oh, this is kind of what I was hoping you wouldn’t do with it’. Then, I kind of gave him some direction, which he took in the most wonderful spirit of collaboration. So he went away, worked his butt off and came back with a lead bass part instead, in the song “Fruit Loops,” actually. The rest of that song is kind of structured and so repetitive that what I was looking for was for the bass to weave a kind of aural narrative through it. And that’s exactly what he did. I was like, ‘oh man, this guy rules.’ [laughs] I sent it to James, and James was of the same opinion. Then we just carried on working with him and he’s a killer bass player.

JT: We didn’t get so lucky on the piano front.

RCU: You had to learn it yourself, right?

NM: I didn’t have very long to do it, but yeah. I tried to teach myself as much piano as I could, without any theory whatsoever. Just by feel, vibe and thinking,‘what will both hands do at the same time?’ And you know, I think there are some moments where it’s like, ‘oh, I can’t believe I got to do that’. There’s a bit in “Michael Landon,” where I’m playing four with my left hand and I’m doing triplet runs with my right. I’m like, ‘yes!’ I feel like I really nailed that.

JT: I’m going to embarrass Nick, because he’s one of these guys that you, as a musician, hate him because he’s like, ‘what’s this a bassoon?’ And he suddenly sounds like he’s in an orchestra. Right? Like he just picks stuff up.

RCU: Are there plans to tour again? If so, what configuration would you have as a touring band at this point?

JT: We’re definitely going to tour for sure. I think we’re both climbing the walls. Touring is something I’ve probably taken for granted. I’ve been touring since 1996, and this is the longest stretch I’ve ever gone without touring. It’s like the old Cinderella song. You don’t know what you got til’ it’s gone. You know, I really do miss the adventures of touring. I even miss the mediocre shows in the flyover country. I just miss being out with my friends and stuff. So I’m definitely eager. I know we want to support this record on tour because we’re really into the record and we want to, you know, go out and meet people like you and do our thing. Obviously there are a lot of logistics involved, but as I said earlier, there’s always been a ton of logistics involved for this band. As far as when and how, I’ll let Nick feel that for now, that’s the harder question.

NM: We want to go to the UK, just because I think there’s an opportunity there for us to do it. I think here in Spain, there is potentially an opportunity to do that. We’ve been talking to a couple of bookers here. I think we both would like to at some point pick up on the West Coast tour that we had to cancel due to COVID. We already made some connections with people. I dunno what will happen when, but I imagine there’s going to be at least some European dates at the beginning of next year and some US dates. I dunno how much later on in the year.

RCU: Oh, well I am extremely excited for that. It’s been way too long. I think we would all be very happy to see you guys out here soon. Something I’ve been wondering is how long have you had these songs ready to go? Were you sitting on any of them for a while?

NM: James’ were all percolated. None of mine were. The way James writes is like, bam, bam, bam, bam song’s out, song’s out. He’s like, ‘finished this song. Right? Next!’

He was already releasing half of that stuff as demos digitally. I’m more of a build-as-you-go kind of guy. So I was sending guitar parts to Jake Morris, who played drums, and Jake was sending drum parts back. I was kind of working on vocal ideas and then sending them to James to do. James got my songs last out of anybody who played on the stuff. So mine didn’t sit around at all, but doing this remotely, I was able to completely change some of the songs.

RCU: Speaking of some of the songs, I’m really curious, what’s the story behind, “Bama Yeti?” It’s such a great song and a super fun concept, and I’m just really curious about where it came from?

JT: Thanks. Yeah, that’s actually kind of a true story. I was visiting my in-laws in Samson, Alabama, which is about as far south as you can go before you hit Panama City. It’s like three hours south of Birmingham. I was sitting with my father-in-law, who has since passed. And he used to listen to the police scanner and the early morning radio shows, and there was a Bigfoot sighting in a small Southern town. There was an argument because people from Florida, in Defuniak Springs (which I referenced), were arguing that it must have come from Alabama, because they wouldn’t have a Sasquatch in Florida. It was just so territorial and so funny. I just had to imagine what the police station might have been like getting all these calls.

RCU: That’s great. I said this on Twitter recently, for some reason, it just made sense to me that you guys would have a Bigfoot song. For the longest time, I have associated them with your sound. I think while listening to the other albums, I would get this mental vision of like Sasquatch hanging out in a Florida swamp just grooving along to the song. It’s Sasq-rock, if you will

JT: Sasq-rock. I like that. [laughs] That’s good…By the way, I’m not a believer or a nonbeliever. I’m Bigfoot agnostic, for the record.

RCU: Oh, hey, that was going to be my next question. Do you believe? [laughs]

NM: Well, what’s funny about that song is that, uh, the first time I heard it, the melody’s so beautiful, that it made me cry, and I wasn’t even really paying attention to the lyrics. The first time I listened to it, I was just like, ‘oh my god, it’s so nice.’ And then I listened to it again, and was like, ‘this is hilarious.’ So it’s like such a weird mixture of emotions.

RCU: There’s definitely a One Eleven Heavy guitar sound, and I think it’s very prominent on this album, particularly on “Fruit Loops.” I feel like it’s especially present on that track. It’s like a rubber band stretched across like a tennis racket. So I was just wondering, how did you come across that sound? How did it become like such a signature aspect to the band?

NM: I actually think it’s 50/50 because I think there is such a disparity between the way we both play. The way the sounds that we draw from guitars as well. The bounce thing I think is because for the last five years, everything I’ve written, if it didn’t already have a swing rhythm when I first wrote it, I would experiment with putting a swing on it, and it’d always sound better with a swing [laughs] So I think there’s one exception, the jam at the end of “Chickenshit,” from the last record, we go into kind of a straight 4/4, and it sounds really different to anything else that I’ve written at least. I think that’s the only thing that I’ve written that doesn’t have a swing on it. So I think there’s partly that, and I think that that has rubbed off on some of James’ stuff as well.

I think in terms of actual sound…technically, I tend to prefer a clean tone with a lot of compression. So I kind of get that like, chicken picking style, but with also a lot of natural sustain and stuff like that. So I like that kind of tone. I think I’ve adjusted my tone to be a little less shrill than it used to be in previous projects that I’ve been involved in. James has a really cornered that little niche in terms of a piercing wire sound.

JT: I like a good mid-range-y honk, you know? I don’t think it’s kind of like the residue of being into metal when I was a kid or something. There’s just a way I play, and a lot of the guitar players I really like are people like Zappa. So I do like that honky mid-range thing—my wife can always spot it. When I play her even One Eleven Heavy live shows, she’s like, ‘oh, there’s you, there’s your sound.’ And she doesn’t necessarily say it in a complimentary way. [laughs] I think that’s good because if you ever look at two guitar bands, historically The Allman Brothers, Television, etc, they always sort of sit in a different sonic space, at least the good ones do. I think for us, we came upon that almost accidentally. I don’t think we planned like, ‘okay, I’m going to stay kinda lower and you’ll stay a little more cleaner and I’ll be honky.’ Like Nick said, we’ve always kind of played that way and it just works well together. I think, because there’s a lot of difference.

RCU: Yeah. That’s beautiful. Then the solos, I think more so than on the previous records, go so hard. They’re so lived in and emotive, like you’re throwing your entire heart and strength into each and every note. I think that’s especially noticeable on “Fruit Loops,” once again, and so I’m just curious, what’s going on there? What led to these ripping and cathartic solos?

NM: It’s funny, you mentioned that one, because that’s the song with the most fucked up solo on the record. I mean there are tons of notes in there. I just wanted to leave them in. Well, I think my favorite solo on that record is in”Tyrant King,” just because probably my most fluid piece of guitar playing in this band, and because I did it in one take and it was the first take. You know, when you get into the end of a solo and you’re like, ‘holy shit. I think I’m going to make it all the way to the end!’ [laughs] You’re like, ‘oh my God, I’m going to get to the end of this solo without completely fucking this up! And it’s going to be exactly what I wanted to be!’ And then when I heard it back, it was. So that’s really rare. Exciting.

On “Fruit Loops,” I had no idea what I was going to do. I hadn’t practiced it. I was just like, I’m going to do a solo now. And then just hit record and went for it. It was all over the place and when I played it back, I was like, this is so riddled with mistakes, but I really, I really, I really liked the way it came out. I felt like there were points where I was really reaching up the neck and I was like really digging in with a pick, really digging the guitar but I think like you say, I think it comes through.

RCU: Like all good records, you can listen to the new LP in a lot of different moods and get something slightly different each time. During my most recent listen, I felt like I could detect maybe some hints of Neil Young and Crazy Horse. Are they an influence on you guys at all?

JT: Oh dude. Yeah. I have a What Would Neil Young Do? tattoo.

RCU: Hell yeah. There you go.

JT: [laughs] I mean, that has more to do with his willingness to get off of a plane if the vibe felt wrong. I also got that when I was like 20. So before I realized the guy was a millionaire when he was 16, so he could totally get off the plane whenever he wanted to. [laughs] I think Neil’s one of the major touchstones for both of us.

When Nick and I met, the reason I knew we were going to start a band at some point, it was years before we actually started a band, was because we had all the same favorite bands, you know? And Neil’s obviously somebody that we definitely share. I don’t listen to a ton of Neil these days because it’s so…I mean, I grew up listening to him. My uncle was into Neil Young. It was like some of the music I had around the house. As far as songwriting goes, he’s my north star. He’s probably the reason I started writing songs. So it’s an inescapable influence for me. I don’t learn anything from that music now. I don’t mean to sound arrogant. I’d rather listen to some prog or death metal or jazz thing that I’m going to be like, ‘how the fuck did they do that?’ For whatever reason, when I listen to Dylan and Neil, who are obviously gods and some of the greatest of all time, I just don’t learn anything.

NM: That’s funny. I feel like the exact opposite. I feel like some of the more out shit is the stuff that I felt like I wanted to explore when I was younger. And I think that as I get older, the nuances of that songwriting is something that I’m just like, ‘okay, I really have to catch onto how this happens.’ And you know, how the stars align in a song whereby it’s not just about what’s been played and what’s been sung, but it’s about how the note is hit, whether it’s vocally or on whatever instrument. Those things that I think I missed when I was younger. I actually listen to more Neil now than ever.

JT: The recording. Do you mean the recording, the recording or the writing part [of Neil’s music]?

NM: I think I all, all of it. Yeah. Both. I think because arrangement as much as anything. The where and the way a note lands, you know, the cadence. Also the writing for sure. I want to be a better writer. I also think what I have to learn from a lot of those records is about the way that certain choices are made. The performative choices. Because a great song played badly is a shitty song.

JT: Yeah. Now I’m with you. I’m with you on the arrangement and the recording part, because it is always those things that kind of give me goosebumps, like the way somebody phrases a word. I’ve studied that a lot as a person who sings, like I’ve listened to people like Leonard Cohen or even Daryl Hall. It’s like, ‘why does that bridge get me so, so much?’ You know? It is all in the phrasing. I just mean as far as the writing goes. We talked before about how the guitar for me was just a means to an end, like I was not a dude that played along to Skynyrd records or Sabbath records, even when I was a kid, I just wanted to write songs and the guitar was the easiest way to do it.

So for me, I’ve, I’ve always been listening to the words and the construction and even the stupid nerdy things. Like, why is this track two? What makes this a side ender? I’ve like always studied that. So for me now, when I listen to bands like Magma, I’m like, ‘what is this music? And how do I find a way in?’ So I guess it’s just my differences as a listener versus a writer. It takes a lot for a singer-songwriter to keep me interested. That’s just the facts. I mean, again, that sounds like a dick thing to say, but it takes a lot for like, a white guy on a stool with a guitar for me. It’s a tough sell for me because I don’t really learn anything, you know?

RCU: So within the music community that you yourself feel a part of, are there any changes that you would like to see?

JT: Yeah. I think the problem is more in the ecosystem than in the community. I feel like the bands don’t have anything to worry about. I feel like the artists are doing what they’re going to do, and it’s honest and it’s good. I don’t think there’s really anything to me, but I think that the sort of ecosystem around it needs to improve. I’m not going to go on a rant about streaming and Spotify, but I mean, that’s obviously where I’m going with this. I think that art requires patronage and now more than ever, because now, there’s just so much stuff [available to listen to], but that makes it difficult for people to survive. I mean, I know Nick is the same as me and I’m not speaking for the whole community, but we work so we can work.

We only want to make money from the record so we can go back into the studio or buy new gear to make more records. We’re not saving up for a Lamborghini. So I feel like, because of that system, we really need something in place. Bandcamp is a good start and Patreon is a good start, but it’s really difficult to survive as a mid-level band or an indie band that’s just starting now. It’s harder than it’s ever been, probably since the Stovall Plantation days. You know what I mean? It’s impossible to bring a five piece band on tour, unless you’re Arcade Fire. That’s a new thing. Nick and I were both in bands the early ’00s and the late ’90s, and we toured in unpopular bands and we came home with money, you know? Just, something’s gotta give with the way that records are being sold and things are being monetized. So as far as the community goes, I think the bands are doing great. I think with artists, more the merrier, but we need to figure out something on the top level because we need voices beyond just famous and rich artists, you know?

RCU: Totally agree with that.

JT: That’s my rant.

NM: Yeah. I think there’s a simple graphic you can draw of what’s actually taking place, and I think that it’s just a funnel. All of the funnel is going in one direction and that’s it. And it’s as simple as that. I think people in the underground hate the idea of a music industry. As soon as you use the word ‘industry,’ it makes people’s toes curl. But the truth is, let’s refer to it as an ecosystem like James did, we had a situation where there were many, many independent record labels. There were different distributors all over the world. There were different physical outlets where you could buy music. Everybody had a role to play, and there was a little bit of something for everybody to be able to just get by doing what they were doing. Even if people had jobs and didn’t do it full time, they could still go on tour. Like James said, you weren’t working to play music. That infrastructure has just been stripped bare now, because of digital culture. Not that I’m some kind of Luddite, I realize all the great that the internet brings to the world. It has enabled us to be able to do this for me and James, to even be able to make music together in circumstances is amazing.

RCU: What’s coming along next after the album released for you guys individually and as One Eleven Heavy ?

NM: James has a new record coming out.

JT: Yeah. I have a record, probably my first nominally solo album since 2017. In January on Kill Rock Stars, under the name James and the Giants. It was produced by Jarvis [Taveniere], from Woods, who is an old friend. Beyond that there’s a One Eleven Heavy tour.

NM: He’s not going to move to Spain because I’ve been trying to get him to do that for the last four or five years, but I am at least going to drag him kicking and screaming to come and record here.

JT: I’m ready.

NM: I’ll tell you what I want. I want to make an album here. I want to spend some time doing it. I don’t want to rush it through. I want to take a long time making a really good in-person record. I would like to play a residency. Nobody does residencies anymore. I’d love to have a residency so we can, so we can sit on our butts during the day and then work at night.

JT: …and unloading gear. I told Nick I’ll book my flight to Spain, as soon as he sends me a photo of the largest industrial air conditioner that Spain has being delivered. That’s the day I’ll book my flight, because that’s my only stipulation. I can’t do the heat .

NM: [laughs] Yeah.

JT: Nothing’ll make you feel more American than going on tour in Europe and being like, I cannot sleep in this. That’s the only time I become like a diva on tour. Maybe Nick can say otherwise, but if there is no air conditioning, I’m no fun.

RCU: Yeah. I hear that. When I was in England recently during that big heat wave, a hotel we were staying at said they had air conditioning and it was all over in their advertising. Then we got there. It was just in the lobby.

JT: Maybe you could sleep there. I guess [laughs]

Big thanks to Nick Mitchell Maiato and James Toth for taking the time to hang and chat with me.

Don’t forget to preorder Poolside on vinyl CD or digital today.

-KH